Picasso is everywhere you look this summer. In addition to four exhibitions in the UK, his works were also featured on the BBC One television series, Modern Masters that explored the life, work and lingering influences of a select group of modern artistic giants. The exhibitions explore Picasso's printmaking in context with his renowned contemporaries (such as Matisse), relationship with women, late craftwork and sculpture in Vallauris, which was altogether tame in comparison and politics.

The most intriguing debates ensued in conjunction with the exhibition Picasso: Peace & Freedom at Tate Liverpool, which addressed the artist's communist party affiliation specifically during the cold war. David Caute, author of The Dancer Defects: The Struggle for Cultural Supremacy During the Cold War, begs the question, how could Picasso have remained a communist when the Russians despised his art and he despised theirs? He argues that Picasso's victims are passive and that was not what communist art should be about, according to the Russians that is; art should be about struggle and resistance. Pacifism was just not admired by the Bolshevists.

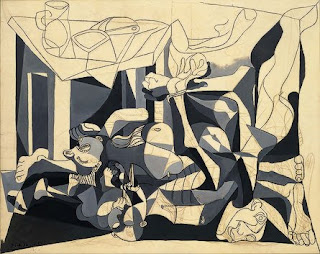

They preferred the social-realist genre of painting, which depicted the working class and images of national pride. For example, tracker drivers, haymaking and Lenin proclaiming Soviet power were acceptable subject matter. Picasso's paintings, such as Massacre in Korea (1951) depicted passive victimisation, and often substituted human figures for animals or fragmented abstractions. The Russians preferred human beings presented realistically.

The most controversial question, which particularly overshadows Picasso: Peace and Freedom is - just how much of a communist was Picasso?

Picasso joined the Communist Party in 1944, which at the time was in tune with his anti-fascist convictions, namely against Franco and the Spanish Civil War. His loyalty to the Party is another story, one that Picasso remained ambiguous about himself, thereby making it even harder to explain on his behalf. It is worth considering that Picasso and his closest friends were members of the French Communist Party and communists were notably anti-fascist.

It has been speculated that the Party used the naive Picasso as their front man due to his fame and popularity, although it is hard to believe that he could be persuaded to affiliate himself with anything that he was not committed to supporting for his own personal reasons.

The Spanish Civil War marked a change in Picasso's political engagement with art. Until the creation of Guernica, Picasso's lack of concern for politics was evident. His dealer, Daniel H. Kahnweiler, is famously renowned for insisting that Picasso was the most apolitical man he ever met.

The conflict in Spain resulted in Picasso's refusal to step foot in his home country while Franco was still in power, thus he never did return. Guernica is his most outwardly political work of art and yet even this work is subtle in that it does not depict a specific enemy or any symbols of reference to the enemy.

Sadly, Guernica was absent from Tate Liverpool's exhibition, simply because it is too fragile to travel. However, its influence has spanned the decades, not least due to the timeless nature of its image, and still packs a political punch today.

The painting inspired a site-specific artwork at London's Whitechapel Gallery, which ran from April 2009 through April 2010 to commemorate its first and only visit to the UK in 1939.

The Bloomberg Commission, The Nature of the Beast, featured a meeting space for public gatherings, which referenced key dates and events in the Gallery's history designed by artist Goshka Macuga. A large-scale tapestry depicting a replica of Picasso's Guernica, originally commissioned by Nelson Rockefeller in 1955, was the main focal point. The gallery originally hosted the painting to encourage support for the Spanish Republican forces and in protest of Fascism.

In recent years, the tapestry has proved to have the same controversial value as the painting itself. Rumour has it that Secretary of State Colin Powell requested that Guernica be covered during his speech regarding weapons of mass destruction in Iraq at the United Nations Headquarters in 2003. Supposedly, this was a request by the camera crew to ensure a cleaner image on film but in reaction to this news, an artists' collective in Los Angeles erected an image of Guernica on a billboard at the junction of Sunset and Hollywood Boulevards in protest of both war and censorship.

Picasso: Peace & Freedom attempts to apply the same political credence attached to Guernica to the large body of works on display throughout the exhibition. Although, there are works in which political references have become attached, such as Picasso's Dove of Peace, there are many forced examples. For instance, renditions of paintings by Delacroix, Velasquez and Matisse do not seem to adhere to the political theme but are more along the lines of appreciation for art history and homage to the Old Masters. Further, curators reasoned that Picasso's adaptation of Manet's Dejeuner sur l'herbe was inspired by Manet's political views surrounding the Paris Commune in 1871.

The Rape of the Sabines and Lobster and Cat were linked to the Cuban Missile Crisis primarily because they were painted in the early 1960s. There is a gallery dedicated to "Mothers and Musketeers" depicting images of female nudes and soldiers which curators claim to represent Picasso's hatred of war and support of women's liberation. These loose associations demonstrate desperate attempts to pin politically significant messages to all of the works on display, which sadly falls flat.

Paintings such as Charnel House, which depicts the slaughter of a Spanish Republican family and a series of twisted cockerels with their necks slit are more obvious allusions to war and suffering although they maintain Picasso's subtle ambiguity, leaving it up to the viewer to attach meaning. Even Picasso's double portrait of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, the American communist couple executed for conspiracy to commit espionage in 1953, is a simple line drawing with no outwardly political message.

The most politically charged of all was the gallery dedicated to promotional objects such as posters, photographs of Picasso speaking at peace conferences and newspaper clips of sketches, which most convincingly attested to Picasso's communist activity.

Nonetheless, in contradiction to being an artistic machine promoting communist propaganda, his portrait of Stalin printed in a communist newspaper in 1953 outraged the Party as they saw the drawing as crude and dishonourable. Picasso had no reaction to the backlash of criticism, which leads one to believe that it did not bother him in the least.

The general message is that although Picasso was a confirmed communist, he made no commitments to the Party with regard to how he was going to create his art. It was very much on his terms. His political statements were deliberately ambiguous - as were his responses when he was questioned about his work in general.

His communist involvement was more in support of communist ideology than its actual practice and, above all, against fascism, which is evident in the fact that he chose to live his life in socialist France rather than his home country, Spain. His investment was social and personal not outright political. This debate over Picasso's politics, however, becomes problematic when art historians and critics concentrate on dissecting Picasso's political position while analysis of the actual works of art fall to the wayside and is precisely the flaw of Tate's exhibition.

Piccasso's "politically charged" works are worth appreciating in terms of their composition, style and symbolism. The works speak for themselves in terms of what they meant to their audience at the time and what they have come to symbolise.

When asked if she can separate Picasso the artist from Picasso the grandfather, his granddaughter, Diana Widmaier Picasso, who wrote the book, Art Can only be Erotic, argues, "Just like art and eroticism, I cannot separate." The same may be true for Picasso and his politics but ultimately, both for the artist and his audience, it is clear that the art is of foremost importance - this is evident by the amount of works he created and the fact that he worked up until his death in 1973. Picasso was an artist not a politician - an artist who enjoyed exercising his creative freedom.

01.07.2010 Stephanie Cotela Tanner

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento